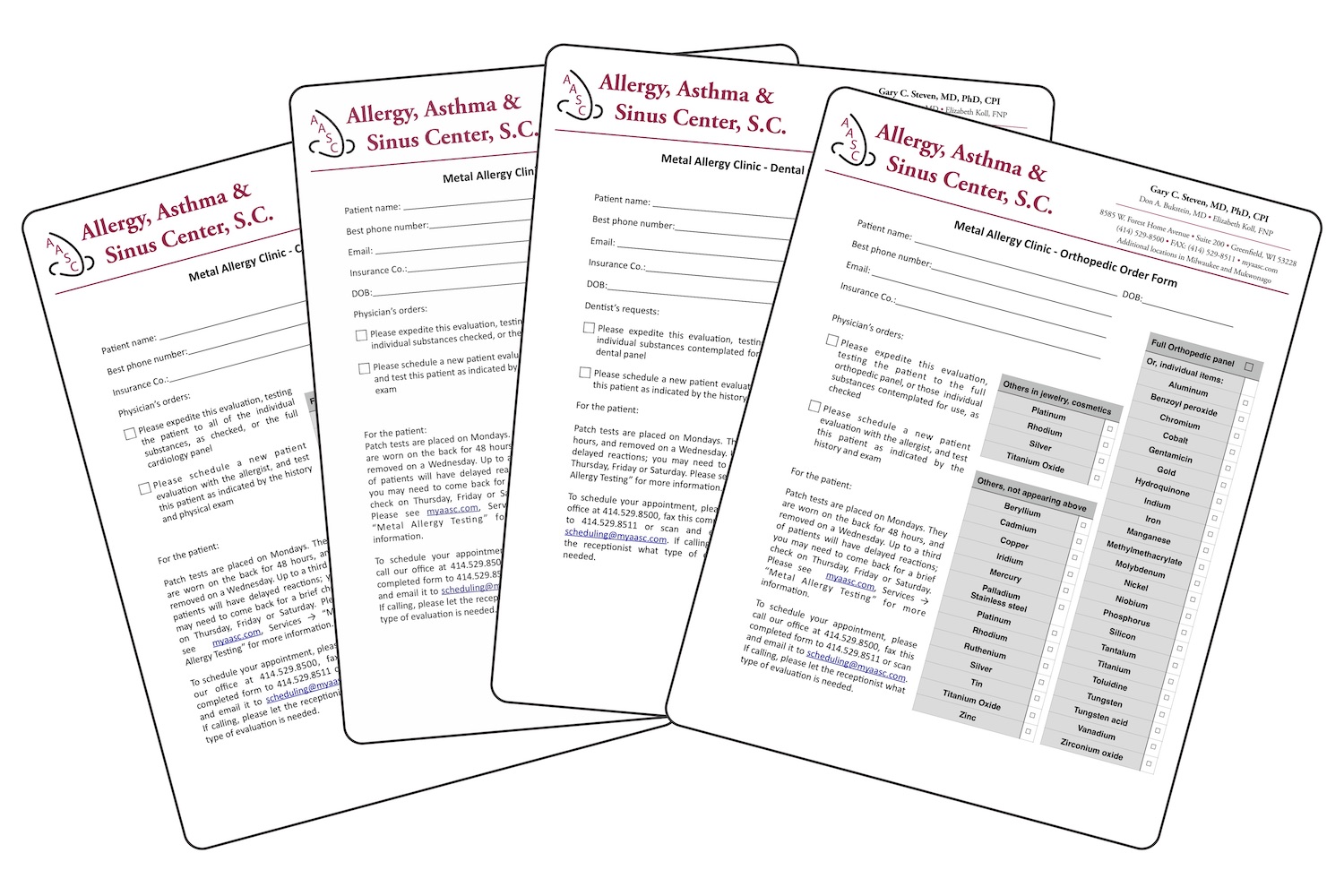

Testing is best performed two weeks before surgery to determine if a given patient has an allergy to any metals that may be implanted. We have done extensive research into the types of materials used in various specialties – orthopedics, cardiology, dental, and gynecology. When an implant by any of these specialists is considered, it is helpful to test at a minimum to the materials that are intended to be implanted. Preferably, the patient will opt to receive testing for the entire panel of relevant materials. For example, if a patient is going to receive an artificial hip, we would test all of the materials used in orthopedics. That way, if a patient is shown to be allergic to the metal being considered, we have already tested them to the alternatives, so the surgeon can choose an alternative material to which no reaction occurred.